I walked into my first job at a leading NBFC in India with Java on my résumé and .NET on the floor. I didn’t know .NET yet, but I did know how to solve problems, read code, and learn fast. The interview leaned on those fundamentals data structures, design basics, trade-offs. I got the offer. Day one wasn’t “hello world.”

It was: “we’re moving this thing to .NET Core start here.”

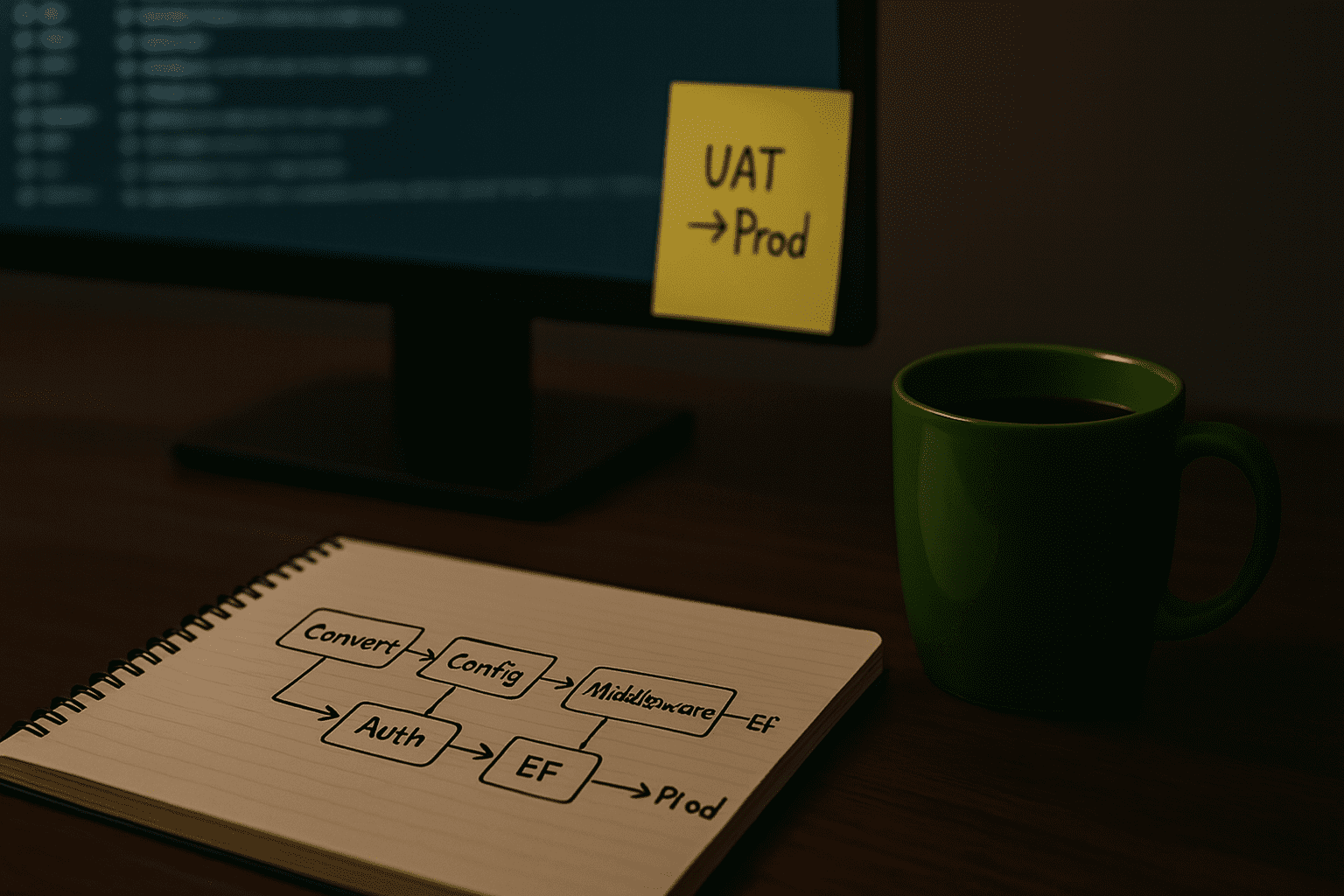

The migration was my classroom. I began where most real work begins: with something that already ships. I converted the old project files to the SDK-style .csproj and replaced the sprawling web.config with appsettings.json plus environment-specific overrides.

I learned why Global.asax gave way to Startup.cs, how middleware is ordered, and what happens when you put something in the wrong slot. Some libraries had no .NET Core equivalents; I found alternatives, wrestled NuGet version conflicts, and learned to read the compiler and runtime error messages like a map. Entity Framework and EF Core behaved just differently enough tracking quirks, LINQ edge cases, migrations that I stopped assuming and started verifying. Authentication flows that looked identical on paper diverged in practice; I traced them until they didn’t.

None of this came from a textbook. Either it compiled, or it didn’t. When it didn’t, I learned why.

We published to IIS for UAT on a test machine. I didn’t own hosting or servers; infra did. My job was a clean build, sensible configuration, and enough diagnostics to make issues obvious. UAT was where reality introduced itself: case-sensitive config keys that were loose before and strict now, missing bindings that dev had never noticed, subtle serialization differences that only appeared with real-ish payloads, and a LINQ query that had “worked” pre-migration but broke under EF Core’s translation rules.

I stopped guessing. I added targeted logging with ILogger (and later Serilog/Application Insights), stepped through the middleware to see exactly where requests went sideways, and traced call stacks until the first failure point was in view.

Only after UAT settled down did I take on production responsibilities. By then I’d already watched the app breathe in a near-real environment. Production wasn’t mysterious just louder. The method didn’t change: isolate the failure, reproduce if possible, fix the smallest thing that solves it, verify, move on.

Java helped more than any course could. Interfaces, generics, collections, threading they map cleanly. I kept a translation layer in my head: “In Spring I’d wire this with X; in ASP.NET Core it’s Y.” That kept me productive while I learned async/await, the dependency injection container, and the request pipeline the .NET way.

Working inside an NBFC added the why behind every fix. Debugging wasn’t academic; it protected revenue and trust. If a disbursal queue stalled, loans didn’t go out. If EMI posting drifted, ledgers didn’t match. If eNACH/eMandate setup glitched, customers lost confidence.

Automobile finance added more moving parts: credit bureaus (CIBIL/Experian/Equifax), KYC services (PAN/CKYC), RC/DL verification for vehicles and owners, valuation services, eSign/eStamp, payment gateways, bank APIs, and dealer DMS/OEM feeds.

Integrations timed out, schemas changed without announcements, webhooks returned “success” but didn’t post anything, and idempotency broke under retries. Every one of those failures looked like “random” user errors until logs told a better story.

Even the math could bite. Interest and EMI calculations daily reducing vs flat, rounding rules, part-payments, foreclosures, GST handling hide landmines. A ₹1–₹5 drift per EMI seems harmless until you add it up across thousands of accounts and months. Posting and reconciliation were another hot spot: out-of-order events, double posting under retries, race conditions in month-end batches. Symptoms showed up as GL mismatches, pending queues, or duplicate receipts. Fixes lived at the smallest possible scope: a missing idempotency key, a stricter rounding step, a retry with backoff but only after I proved the failure path.

My debugging loop stayed simple and boring on purpose. Reproduce in UAT with masked, real-like data. Read the logs first application plus IIS to find the first thing that fails, not the tenth. Isolate a single path: one API, one job, one screen. Make the smallest fix that moves the needle. Add or adjust a test (unit or integration) so we don’t trip again. Republish to IIS for UAT, verify with the same steps, then promote to production. When the issue warranted it, I pulled in EF Core query logging to see the exact SQL being generated, or fired up SQL Profiler to catch slow or chatty queries. Most of the time, though, Visual Studio breakpoints, watches, and the call stack were enough.

If you’re making the same journey old .NET to .NET Core start with the bones. Convert projects to SDK style. Move configuration into appsettings*.json with clear environment separation. Replace Global.asax with modern middleware and remember that order matters. Swap incompatible libraries thoughtfully; don’t just “update everything.” Re-test auth flows and EF behaviors in UAT before you trust them. And keep your logging structured from day one so future-you can solve tomorrow’s mysteries without adding print statements everywhere.

For beginners, here’s the only shortcut I know: don’t wait to feel ready. Pick a small project and ship it. Learn by debugging code that people actually use. UAT first; production later, when you’ve already seen the edge cases. Migrate something old to something current; you’ll learn more from friction than from a blank repo. Map what you already know from one language to another so you’re never starting from zero. And help others debug the act of explaining your reasoning sharpens your own.

I didn’t become a .NET developer by collecting notes. I became one by moving a legacy app to .NET Core, publishing to IIS for UAT, fixing what broke, and then carrying that confidence into production. The path was straightforward: ship, observe, debug, repeat.